TNT Residency is an exciting endeavor co-hosted by Transmitter and TSA NY. Sharon Cheuk Wun Lee was the 2025 summer artist-in-residence for the 6-month fully funded 430 square foot studio at 1329 Willoughby Avenue, Brooklyn. Her practice is multidimensional and expansive, from engraving, drawing, to photography, as well as alternative photography and installation that incorporates the ethereal and tangible. The scale of work is confident and deeply personal. Incorporating studied subjects from an ethnographic, geographical, and historical background, to materials that reflect, entangle, and layer personal memories.

TNT: Can you tell us about the mediums you use?

Sharon: My work attempts to slow down images through an alternative approach to materials that is relational, sculptural, and archive-driven. My practice spans engraving, drawing, alternative photography, and installation. Intangible and elusive elements—such as light, rainbow, humidity, conversations, wish-making, and void—are incorporated into my art practice to explore memory and homeland in transit. I often combine industrial materials, such as aluminum, bronze, and porcelain, with organic elements, embracing unpredictability in the face of stability. I focus on the in-betweenness, the joint, inspired by grafting, a horticultural act of cutting, rejoining, and healing to create hybrid species.

I consider the photographic apparatus broadly, as a way to rethink how images are produced, represented, and circulated, from camera-less photograms and primitive camera obscuras to instant Polaroids, copy machines, and satellite street views. I often begin with found images: family albums, historical postcards, satellite street views, museum archives, and herbarium records. These serve as raw materials that I reread and translate, as a way to cope with loss and find a sense of belonging.

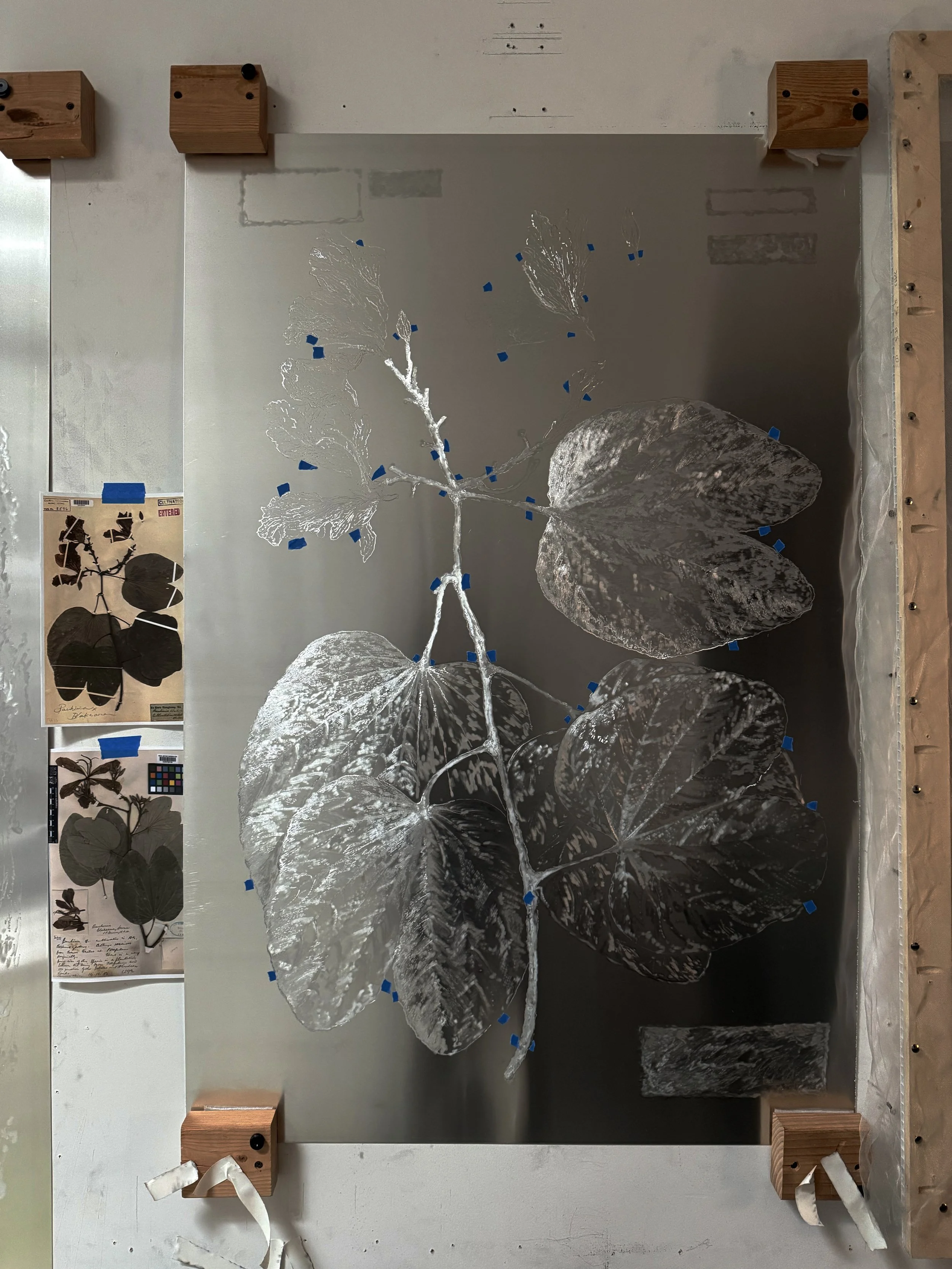

When I engrave images on metal, I think of it as transforming an image into a presence of absence—an airy photograph, a scar, a relic. I imagine this process as sculpting with light: translating and personalizing images through the touch of the hand rather than the precision of camera machines. The engraved lines shift with light and perspective, revealing how images are never neutral or objective but always in flux.

Photo courtesy of the artist Sharon Cheuk Wun Lee, all rights reserved. Image: Artist working in the studio

TNT: Can you tell us about how you incorporate cultural markers and history in your works?

Sharon: Before moving to the States, my work was grounded in my family, my neighborhood, and memories that were close and familiar. After moving to New York, the idea of home shifted but expanded. I often feel caught between categories—every form that asks me to check a box for race, nationality, or gender reminds me how vast the world is, and yet how small those boxes can be.

I’m interested in how power operates within the colonial histories of image-making, circulation, and representation. Through my art practice, I seek to decolonize my understanding of Hong Kong, my hometown, and a former British colony. Growing up, I was taught Hong Kong’s history through the colonial narrative of progress, from a fishing village to a global financial hub. Now, I search for pluralities in histories. I attempt to re-read the history of Hong Kong from an oceanic perspective—through its identity as a port city, through the mystery of its sterile city flower (Bauhinia × blakeana), through its impossibility of classification, and through the mobility of its people.

My recent body of work began with a search in The MET’s collection. Ten years ago, I worked there as an intern, inputting catalog cards into the expanding digital system. Out of curiosity, I searched for “Hong Kong” again after a decade had passed. One of the few results was a hand-colored photograph with “Canton Girl” written on the back. I requested to see the actual object from the Photography Department.

In the museum’s record, everything centered on the photographer: the technique, the date, the work’s value as a keepsake, but nothing spoke of the sitter herself, her story, or her world. When the photograph later appeared in The New Art: American Photography 1839–1910, more information was added; however, the image continued to fulfill the narrative of the empire, and some darker aspects of the history were veiled. In response to the archival silence, I “recolor” the Canton Girl portrait with zip-ties in an embroidery manner.

Confronting this absence, I began tracing postcards of Asian women circulating in global gray markets. There, I uncovered a hidden history of young women’s trafficking and enslavement between Hong Kong and San Francisco in the 19th century—entangled with the Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882 and its afterlives.

In One Face on Thousands of Postcards (2024–25), I focus on three postcards of San Francisco’s Chinatown, dated around 1900, featuring the same Chinese girl carrying a baby—each recolored and recaptioned to conceal histories of servitude beneath racialized fantasy. I reconstructed her portrait using grains of cooked rice that crack and deform over time, questioning the consumption, women’s labor, and visual ecologies behind the portrait.

Image: 1900s postcards collected from eBay

In one of the postcard variations, the girl is cut and pasted into a pink flower garden. My search for that fictional background led me to the Bauhinia × Blakeana, the Hong Kong orchid tree — a hybrid, sterile plant that survives only through cutting and grafting. It has also become a popular flowering tree in California, widely planted as a street tree in parks and gardens for its orchid-like appeal. I consider it a metaphor for displacement and resilience.

In Graft (2025), I engraved this sterile city flower of Hong Kong onto aluminum sheets—a material commonly used in seed banks for storage and preservation—to question systems of control and conservation. The etched image reveals itself only through reflected light and movement, rejecting a fixed perspective and remaining in a state of constant flux.

TNT: Can you tell us about your upcoming works?

Sharon: My upcoming works utilize botany as a lens to examine the past and future of Hong Kong, re-examining its colonized history and exploring the fluidity of belonging. I translate, materialize, and personalize historical photographs through metal engraving. The works are also optical in nature, rejecting a fixed perspective and inviting bodily experience and movement.

This thread can be traced back to Wish You Well (2020), a commissioned project at the Hong Kong Botanical Gardens, a site rich in collective memory and colonial histories. There, I used a rainbow in the fountain, which had been rebuilt three times over the centuries, as an invitation for collective wish-making, asking how histories might be reclaimed through intangibles. “Here lies the rainbow for wishful thinkers” was inscribed on the fountain, and each wisher’s hope was captured in a series of Polaroids, which formed another rainbow. I’m happy the work remains on-site, quietly activating this place. Sometimes, I revisit the fountain virtually on Google Maps—it feels like a keepsake, a small gift to my hometown.

The Botanical Garden was also home to the Bauhinia × blakeana, a flower central to Hong Kong’s postcolonial identity that replaced the Queen’s portrait on the currency. Its origin is mysterious—a single tree was discovered around 1880 near a ruined building on the Hong Kong shoreline, then transplanted to the Botanical Garden.

A hybrid and sterile species, it was propagated only through cutting, grafting, wrapping, and healing, which require touch, care, and time. Every existing Bauhinia tree in theory is a clone of that first specimen—a living-dead “photograph.” I work with these herbarium records from Hong Kong, Kew Gardens, and Hawaii. These records are like the skeletons of ancient memory and identity, while also demonstrating how the dislocated species thrives on different continents, with its showy, deep pink flowers blooming in winter.

Recently, I was drawn to a historical photograph labeled “Possibly Hong Kong” in The MET’s collection. The image shows branches framing the sea from a mountain view—so ordinary, yet deeply familiar. It reminded me of the view from my childhood home, looking down from the hills toward the harbor. It might even depict the mythical site where the very first Bauhinia × Blakeana tree was grown. The title itself, Possibly, suggests both doubt, novelty, and possibility: a poetic opening rather than a limitation.

.

TNT: What has inspired you recently? Any films, exhibitions, music or artist(s)?

Sharon: I often find inspiration in the mundane—in everyday encounters that most people overlook. I try to stay open to what the city offers me. I remember when I first arrived in New York a decade ago, there was more music and graffiti in the subways. Now, much of that has disappeared. I used to love hearing a cello and a plastic bucket drum clash together in the noisy, smelly station. I often pay attention to how people still find ways to leave their marks—engraving initials on the aluminum walls or white tiles on the subway—and how those traces are later removed, sanded down, or washed away.

I grew up in a city where disappearance feels habitual. Things change, vanish, rebuild—the constant cycle of loss and renewal deeply shapes my lens-based practice. Through alternative photographic processes, I aim to address the cultural disappearance that occurs when memory and history are continually obscured by change, media, globalization, and diaspora.

I was deeply moved by Álvaro Urbano: Tableau Vivant at SculptureCenter. The installation was delicate yet powerful—wandering on a ground of rotten apples and shadows of moths illuminated by changing light felt strangely personal. The motif of moths also resonates with me, as they used to keep me company every night at my window. To me, the image of the moth carries both intimacy and fear. In an exhibition I did last year in Hong Kong on the theme of home, I worked with rice and mold fungi to construct a moth, using temperature and humidity to explore ideas of homeland, death, and rebirth.

Jack Whitten’s retrospective at MoMA was another unforgettable experience. The opening line of the wall text said, “Whitten created visionary beauty from righteous anger.” That struck me deeply. There are moments when I feel powerless as an artist, and it’s grounding to be reminded of why we continue to create. Whitten’s process was so meticulous, layered, and experimental. My own practice is very process-driven and material-centered—I’m never satisfied unless I’ve found a new way to work with a material. Coming from mixed backgrounds in photography, painting, and ceramics, I connect with how Whitten manipulated paint almost like a sculptural or photographic medium.

Recently, I attended Tomorrow Comes the Harvest at Pioneer Works, an improvised performance by Jeff Mills, Jean-Phi Dary, Prabhu Edouard, and Rasheeda Ali. It was mesmerizing—techno rhythms entwining with flute and tabla in an unexpected harmony. That spontaneous energy, the way they explored unknown territories through sound, really inspires me to think about how I can bring the same openness and improvisation into my studio practice.

Photo credit: Javier Griffey

![Title: [Studio Portrait: Woman Standing in Profile Holding Umbrella, Hong Kong] Credit line: The Horace W. Goldsmith Foundation Fund, through Joyce and Robert Menschel, 2017](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5488a71ce4b0963c92fc2c62/1763171227254-R2Z5JCN0BDPP2BERGYEH/DP-15801-104.jpg)